After Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff (COAS) General Raheel Sharif’s visit to the Pentagon, Islamabad defense officials claimed that the United States would give Pakistan $1 billion through the Coalition Support Fund (CSF). The officials added that the US would “further give Pakistan used defense equipment to meet its security challenges for which the process had already begun.”

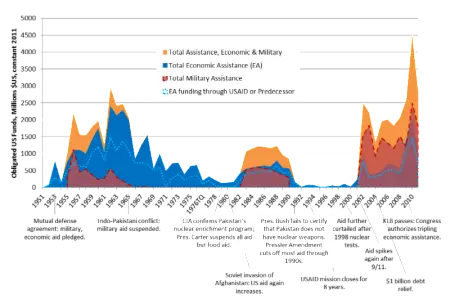

History of US Obligations to Pakistan, millions US$ (2011)

Source: US Overseas Loans and Grants: Obligations and Loan Authorizations (aka the Greenbook)

Source: US Overseas Loans and Grants: Obligations and Loan Authorizations (aka the Greenbook)

And thus continues the annual Pakistan military peregrination to Washington where Uncle Sugar was sure to provide his usual handout to an ungrateful nation. A program that began in 1951 — after which the US has obligated more than $70 billion for military and civilian purposes — can trumpet few successes, if any.

Background — After spending at least $70 billion, American aid to Pakistan has had few successes and many notable failures.

It is generally assumed that the immense amount of US assistance that reached South Asia following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan helped force a Soviet retreat. The Central Intelligence Agency presence, in reality, was quite minimal since it used Pakistan’s military intelligence unit, the ISI, and the port of Karachi to provide arms to the mujahedeen. Financial assistance to the mujahideen movement itself was in large part the work of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states. In the end, it was the American ground-to-air missiles that were decisive in that war. However, since much of US aid to Pakistan has arrived via intelligence agencies “off the books”, the official dollar figure was in fact only a small percentage of US military aid.

Following the Soviet withdrawal in 1988 and the arrest of Pakistani banker Yunus Habib in March 1994, the ISI’s meddling in Pakistan politics was revealed. Habib admitted that he had given Rs 140 million to the Pakistan Army Chief, the very Islamist General Mirza Aslam Beg, for ISI disposal in the November 1990 elections. Since then, nothing happened to reduce the power of the ISI, and to this date the Pakistan military continues to play an unseen hand in Pakistani politics.

Trafficking in Arms And Narcotics — Among the most deleterious aftereffects caused by the war in Afghanistan was the introduction of massive quantities of small arms in Pakistan’s northern provinces, much of which was introduced by the ISI in the first place. Pakistan’s military either turned a blind-eye to the traffic or took part in it. Hand-in-hand with the increase in arms was the creation of scores of arms markets found throughout Pakistan’s northeast — a phenomenon the Pakistan military even today has done nothing to eliminate.

In addition, the Pakistan military took a direct hand in the production and distribution of Afghan drugs. The Pakistan military’s own National Logistics Cell, which had been involved in transporting supplies to the mujahideen, also played an important role in what was no less than the state-sponsored drug-trafficking that flourished beginning with the tenure of General and then Prime Minister Zia ul-Haq. By 1990 it had taken control of much of its manufacturing and distribution. The drug trade provided the investment capital needed to create a really top-tier smuggling network. Its Pashtun gang spread from Pakistan to the Persian Gulf, to Europe and even into the United States. Today, the Pakistani Pashtuns are said to dominate the Dubai smuggling nexus, with Dubai itself having the third largest Pashtun population after Peshawar and Karachi.

In 1993, the government of Benazir Bhutto, with US assistance, instituted a National Anti-Narcotics Policy. It created a number of government agencies to attack both the trafficking of drugs and the burgeoning use of drugs within Pakistan itself. The effort failed. In October 2010, the government, again with US funds, tried again and instituted a new National Anti-Narcotics Policy. While some opium was destroyed, other poppy fields popped up elsewhere. Thus the trafficking of Afghan narcotics through Pakistan and the smuggling of precursor chemicals from Pakistan to Afghanistan continues unabated. And the Pakistan population as a whole has one of the world’s highest percentages of narcotics users.

Since 1995, the US Drug Enforcement Agency has been operating on a $1 billion budget. A significant portion of which (only God knows how much) has been spent on anti-narcotics activity in South Asia, and thus in Pakistan itself.

A.Q. Khan — The Pakistan military involvement in arms sales and drug trafficking was not its only instance playing with fire. Of even greater significance was its support for Dr. A.Q. Khan, the architect of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program.

Although it was known for years that Khan was at work building an atomic bomb, his success was not noticed until 2003, when Libya provided hard information that Khan had earlier provided the Qaddafi regime with “blueprints for a 10-kiloton atomic bomb.” As an added sweetener, Khan sold $100 million in nuclear gear. The discovery led to the quarantining of Dr. Khan, but his work in Pakistan continues.

Military Aid and The Osama Bin Laden Hideout — As can be gleaned from the table on US military aid to Pakistan (above), the progress of US military aid to Pakistan has been little short of a roller-coaster ride.

Washington imposed sanctions and suspended military ties following Pakistan’s 1988 nuclear tests. But in late Summer 2002, and in the aftermath of the 9/11 attack, the US Under Secretary of Defense arrived in Pakistan to revive what had been a moribund Defense Consultative Group. Weeks later, in October 2002, the commander of American forces in Afghanistan, General Tommy Franks, arrived in Pakistan to observe the first joint US-Pakistan military exercises to be held in four years. The alliance was resumed once Pakistan agreed to cooperate with the US in its war in Afghanistan and eliminate the al-Qaeda presence in Pakistan.

As to the latter point, the discovery of Osama Bin Laden’s hideout in Pakistan led many to speculate that senior ISI officials knew of his whereabouts at least as early as 2005. His compound was, after all, located in Abbottabad, a small city where the country’s military academy was located and the military itself was omnipresent.

Following the raid on the bin Laden compound, military aid to Pakistan, programmed at $1.5+ billion for 2013, was blocked until late that year. Aid was only resumed after an October visit to Washington by Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif mended a badly frayed relationship.

There was still the troubling fact that the Pakistan military had done little or nothing to eliminate the jihadist base in Waziristan, or its pied-a-terre in Quetta city, Baluchistan province. In September 2009, an Afghan native and an al-Qaeda operative trained in Pakistan’s Waziristan were arrested for planning to detonate bombs in New York City’s subway system to mark the anniversary of 9/11.

In early 2011 the Pakistan military finally announced the initiation of a campaign against the Tehreek-e-Taliban (TeT) movement in Waziristan. The TeT, called the “Pakistani Taliban,” had previously pledged allegiance to Mullah Omar. He was the Afghan leader responsible for Taliban activity in Afghanistan; he was also head of the its Shura, actually located in Pakistan’s Baluchistan province. Over the years, some 5,000 foreign jihadists were said to have made North Waziristan their home, and they had turned the location into what many analysts called the heart of global terrorism. However, until 2014 the Pakistan attacks on terrorist bases located in Pakistan’s north and northeast were desultory at best.

The recent attacks on terrorist bases in North Waziristan that began in mid-2014 are, according to the Pakistan military, quite the successful operation. However, as no media or foreign observers are allowed into the area, its claims cannot be verified. Nonetheless, a Pakistan news reporter noted that, “Defense officials said US would also give Pakistan $1 billion this year under the Coalition Support Fund (CSF).”

A billion here, a billion there, it gets lost in the shuffle. In the final analysis, one is left to speculate just how the United States has benefited from the military hardware it has supplied over the years, or from its direct and tangential financial support for the Pakistan military.

Foreign Aid and The Obama Regnum — In 2009, at the urging of the Obama administration, the US Congress agreed to spend $1.5 billion annually for civilian aid in the years 2009-2013. Richard Holbrooke, who had just been named special envoy to Afghanistan and Pakistan, initiated a change in program emphasis. Concerned that “all of the money the U.S. was pouring into Pakistan hadn’t improved America’s image,” the envoy took matters into his own hands. He began in March 2009 with a meeting of USAID officials active in Afghanistan, Pakistan and the Central Asian republics. A participant later stated, “He thought everything we were doing was a failure.”

Aid was directed away from involvement with international aid agencies and to a program that delivered more assistance to local organizations and the Pakistani government. He wanted projects, “more aggressively to show ordinary Pakistanis that they are benefiting from U.S. funds.”

Source: “Setbacks Plague U.S. Aid to Pakistan” the in Wall Street Journal, January 21, 2011

Source: “Setbacks Plague U.S. Aid to Pakistan” the in Wall Street Journal, January 21, 2011

Included in the forward-looking package was an energy plan that USAID prepared. Then, as now, the Government of Pakistan was in the midst of a severe energy crisis. Thus a USAID program to fund large-scale energy projects (1,300 megawatts) and deliver electricity to more than 16 million people was welcomed. However, it has yet to make a significant impact on the ephemeral supply of electricity to the Pakistani populace.

USAID projected that about 900 megawatts would be added through renovation and rehabilitation of trouble-plagued Tarbela Dam located north of Islamabad on the Indus River. Assistance was also given for the Jamshoro Thermal Power Plant in Sindh, and the Muzaffargharh Thermal Power Plant in Punjab. Additionally, USAID has provided funds to complete the Satpara Dam in Gilgit-Baltistan (US$26 million, agreement signed in 2011), and the Gomal Zam dam in South Waziristan (US$97 million in 2013). If last month’s energy blackouts throughout Pakistan are any indication, then the US aid for a new dam and energy production is a drop in the bucket of Pakistan’s energy needs.

There is no present indication that the USAID program for Pakistan has shown much improvement since Holbrooke initiated his plan. It seems that his death in December 2010 put an end to his initiative.

Afterward — On the eve of Obama’s visit to India, the Washington Post noted: “As Obama visits India, Pakistan looks to Russia for military, economic assistance. As the United States forges closer ties to India, neighboring Pakistan is looking for some new friends. Officials hope they have found one in Russia — a budding partnership that could eventually shift historic alliances in South Asia.”

One would think the Russians learned a lesson in Afghanistan. Putin would be wise to think twice and avoid entanglements in South Asia, especially the Pakistan snake pit. Leave it to the Pentagon and Foggy Bottom to play the fool.

* Full Disclosure: Noted in my checkered employment history is the fact that on three occasions I have been an employee of the Agency for International Development.

* J. Millard Burr is a Senior Fellow at the American Center for Democracy.