While the United States media was enmeshed in the aftermath of the Boston bombing, on April 26, Karachi, Pakistan’s former capital, suffered its own horrific bombing. An explosion at a street meeting of the Awami National Party (ANP), Pakistan’s oldest political movement, left ten people killed and more than forty injured. A bomb using nearly ten pounds of explosives spewed ball bearings and nuts and bolts throughout a crowd massed to hear political speakers.

A spokesman for the banned Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) movement admitted to Pakistan’s Dawn.com that his organization had carried out the attack in response to the ANP’s “secular views.” It was, in effect, the continuation of attacks that the Taliban has initiated with the aim of cowing citizens who might otherwise vote in the upcoming May 11 election.

The TTP has chosen to attack not only the ANP, but the “secular” liberal and middle class Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) as well. On April 25th, the TTP attacked the MQM office in Karachi. It was the second such attack on the party apparatus in three days and followed MQM leader Nasreen Jaleel’s statement publicly blasting the “Talibanization of Karachi.”

It is also true that the TTP has demonstrated little use for the powerful Jamaat Ulema e-Islam (Assembly of Islamic Clergy), an Islamist movement organized by Pakistan’s Debandi sect. It has created and supports its own madrassas (Islamic schools) and Taliban movement.

MURDERERS AND THE COURTS

Earlier in the month of April the Pakistan Daily Times reported that 71 jailed assassins were released on bail. Ironically, while the 71 jailbirds were released, Pakistan’s Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad ordered law enforcement agencies to arrest scores of lawbreakers whose names were listed in a report that had just been submitted to the Court. The Bench demanded the presentation of data concerning the arrest of 68 murderers arrested during targeted operations conducted in March.

The Court sought to learn just how many of those arrested had been charged before the different city courts, including anti-terrorist courts. Because many of those arrested in March had been released on bail in April, the media, and assuredly the public, had reason to be skeptical of the judicial system. Revolving door justice had led the release on bail of a prisoner who had pleaded guilty to the murder of 115 people, and another prisoner who had admitted to killing 47.

An exasperated Pakistan Chief Justice was led to wonder, “How would law and order in Karachi improve when murderers are released because police care only about their promotions and job security?” He concluded, “every act in the city is politically motivated.”

It was common knowledge that the PPP had for years benefitted from and supported Lyari, the smallest and most densely populated of the city’s eighteen “townships” that comprise Karachi. It is the center for narcotics trafficking, gambling and general gang activity. It had thrived ever since Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, pandering to Islamists, banned gambling and alcohol in Pakistan in 1987. The result was that both were driven underground, where they flourish today. In fact, gambling in Karachi is controlled by the police who enhance their meager pay by supervising the dens where mang patta and chakka are played.

NARCOTICS USE

When interviewed in October 2008, the Karachi street-based Human Development Foundation claimed the city already counted over two million young addicts, “and [the] rest of the youth and children are at also at the high risk of drug addiction, as drug trafficking is prevailing in every part of the city.” (PPI, 26 October 2008). Nearly five years later, there is no indication that the number of users has subsided. (The Nation, Karachi, 30 March 2013.). Instead, the price of heroin has fallen to $4 per gram–compared to $100 in Europe and as much as $200 per gram in the U.S.

Of an estimated 25,000 children living on the streets, three-fourths are already said to be addicted. The government’s Anti-Narcotics Force has been ineffectual because they refused to arrest the small drug peddlers. And it is the small fry that sell cheaply small amounts of hashish and heroin (brown and white) that are responsible for the growth of narcotics use. No ethnic community–neither the Bengalis, the Baloch, nor the Burmese Arakan–has been safe from their infiltration. While the upper class prefers popping pills to hard drugs, throughout town the bus stands serve as the nexus of the narcotics trade. On a larger scale, Karachi port serves as a “hub of exporting drugs to different countries.” Of the 580 tons of heroin produced in 2012 in the Afghanistan-Pakistan borderland, about half reached the international market through Pakistan (and less than one ton was seized by Pakistan officials).

Drug abuse in Karachi has created a public health disaster seemingly without end. The nation itself has but three rehabilitation centers, and some 200 private centers, and methadone, the preferred treatment for heroin addiction is generally available in neither service. The unfortunate addicts who are jailed are forced to go “cold turkey”, like it or not.

In early 2013, the heads of Karachi police admitted before the Pakistan Supreme Court that the morale of their men had been shattered since the courts refused to punish gangsters and pushers. Worse, the courts were “sluggish” in the prosecution of criminals charged with murder of policemen. It was claimed that while 162 police had lost their lives in the line of duty, only three killers were brought to justice.

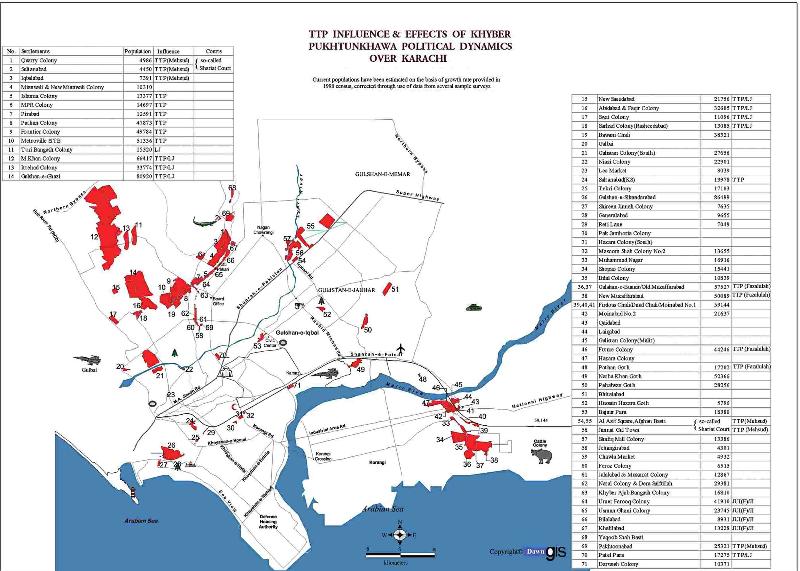

When police officials were queried about reported ‘no-go’ areas within the city that the police would not enter, they were questioned about the existence of 13 areas dominated by gangsters, and 29 areas off-limits to “people of a particular ethnicity.” The officials were hesitant in their responses, unwilling to admit that such areas existed, even though one of the most fearsome places was located across from the Pakistan Naval Base. It was also clear, from a police intelligence warning issued in 2011, that Karachi was about to suffer from an influx of ruthless TTP terrorists from the north. That had come true. The TTP had already managed to infiltrate the previously lawless ‘no-go’ areas of Manghopir and Sohrab Goth and had made them their own.

ATTACKING THE NO-GO ENCLAVES

On hearing the evidence provided by the Karachi officials, Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Caudry was obviously dissatisfied with the anarchy that existed in the port city. It was hard to determine whom he considered more lax, the police, or the Ranger leadership assigned to the city. He ordered them both to initiate at once an operation to eliminate the ‘no-go’ areas. It was a start. However, without the national will to eliminate crime and corruption in the city, and the public safety and judicial personnel needed to effect a change, there was little optimism that the situation would soon improve.

A major reason for pessimism is that the TTP have already become major players in the sale and control of land, an aspect of the Karachi economy long considered the domain of investors “with close links to the major political parties and forces amongst the establishment.” (Dawn, 31 March 2003) According to one news report, there are at least thirty TTP factions now present in the city. Most are controlled by factions loyal to terrorist leaders Hakimullah Mehsud or Mullah Fazlullah. They are ruthless elements. Even more ruthless than the gangster element that had been running the city.

As things now stand, the betting is that the situation in Karachi is bound to get worse before it gets better.