In a thought provoking essay titled “The P-Word” published in the American Thinker blog, Ben Cohen offers a précis of the history of a multi-ethnic multi-cultural Middle East. He suggests that a solution to the present Syrian cataclysm would be “to partition Syria into separate states which would allow the different sides to live under laws and governments of their own choosing;” a large Sunni Arab state controlling the vast majority of Syria, with small Alawite, Druze, and Kurdish states controlling the rest.

Cohen notes that Druze are concentrated in the south and Assad’s own Alawite minority along the coast near Latakia. He notes, almost en passant, that the Kurds concentrated in Syria’s far northeast could be “given a small area in the north where they could live according to their customs and make Kurdish the official language.

The excision makes a great deal of sense and the Syrian Kurds (and the Kurdish minorities in Turkey and Iraq) would like nothing more than for that to occur. Cohen concludes, “The future states would be smaller, but they would be wealthier, safer, and better for the people actually living in them: and isn’t that the point?”

*****

At present the United States has no greater ally in the Muslim world than the Iraqi Kurds who occupy a region whose western border abuts Kurdish Syria. Following Operation Desert Stormand well prior to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, the Kurdish region survived as a virtual protectorate of the US military. The Syrian Kurds well recognize just how that American protectorate and its “no-fly zone’ halted the intrusion of Iraq dictator Saddam Hussein and made possible the creation of what is now a semi-autonomous Kurdish state within Iraq.

If the taxi drivers in Irbil, Iraq, can be believed, their brothers in Syria would welcome the protection of an American umbrella over their region. But given the US disinterest in direct involvement in the Syrian civil war, and the potential involvement of Syria, Iraq and Turkey in any move to create a Syrian Kurdistan, such an event, though welcome, is highly unlikely.

Still, the pot has begun to simmer. In a recent worrisome event, in mid-July 2013 the quiescent Syrian northeast was roiled when a Syria Kurdish militia battled (and defeated) an Islamist force that had entered the Hasakah region. Hasakah town is located about 30 miles from the Iraq border, and about 150 miles from Mosul. There is little doubt that the Syrian Kurdish militia is receiving support from their brothers in Iraqi Kurdistan. Other reports had it that nearby Ras al-Ain had been captured by forces under the control of the indigenous Syrian-Kurd Democratic Union Party (PYD).

The action was entirely too close to the Syria-Turkey border for comfort, and Turkey issued a warning to the PYD, which it called a “separatist terrorist organization” with links to Kurdish militants in Turkey. Reportedly, Turkey feared “the emergence of yet another autonomous Kurdish region would flame the embers of a long smoldering Kurdish revolt inside Turkey itself.”

A Remembrance of Things Past

In November 2011 it was reported from Ankara that the government of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan had secured a major diplomatic triumph as U.S. President Barack Obama agreed to move U.S. Predator drones then stationed in Iraq to the Incirlik airbase located in Turkish Anatolia and north-northwest of Aleppo, Syria. As Dorian Jones of RFE/RL reported in November 2011, “the drones are seen by Ankara as a decisive weapon in its battle against the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), the Kurdish rebel group.” Jones added that, “The atmosphere seems to be that Turkey did indeed receive a positive reply from the U.S. that some of those Predators currently in Iraq will be transferred to Incirlik and potentially made available for the use of the Turkish military,” says former Turkish diplomat Sinan Ulgen, a visiting research fellow at the U.S.-based Carnegie Institute.” Ulgen noted that Obama was “rewarding Turkey for its support in the region, in particular its decision to participate in NATO’s antimissile system, which Washington says is aimed at countering threats from rogue states including Iran.” Before the US drones arrived, it was claimed that Turkish Prime Minister Erdogan’s requests for their use had been rejected by Washington that claimed it needed them in the war against the Taliban and Al-Qaida.

The Kurdish Homeland

It was unclear, both then and now, how the drone program at Incirlik, the huge airbase utilized by US forces for decades, would serve both American and Turkish interests. Would Turkey allow the U.S. to unilaterally operate drones from Turkish territory? Would the drones be used to track the activity of Turkish Kurds? Would there be dual-use of drones? Would the United States lease Predator drones to the Turkish military forces for their own use?

*****

While there is a general perception that Turkey has been a Western ally of long duration, beginning in the nineteen sixties the Turkish government and a significant percentage of educated Turks wanted little more to do with NATO or the United States. And that meant no more military assistance, economic aid, or bilateral trade. The anti-American sentiment grew with its involvement in the War for Afghanistan. It accelerated in the nineteen nineties with the war in the Balkans. It was a war in which Turkish politician Recip Erdogan and his mentor Erbakan (both long time members of the International Muslim Brotherhood) played a major role as intermediaries in the Islamist-backed insurgency and in the movement of arms, food aid and funds to the Bosnian, Kosovar and Albanian Islamists. It was the staging point of a movement led by Erbakan and then by Erdogan as the Islamists began to take charge of the Turkish polity and dominate its future.

Given the Obama administration change in policy, the free-ranging Turkish media were confident that drones would soon be put to use in the Turkish military’s unending conflict with Turkey’s rebel Kurds.

The Turkish government had been at war with the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK) for decades, as the rebels sought the independence of a Turkish Kurdistan. The Turkish Islamists detest such US Congressional moves as the Armenian Genocide Bill, its sometime support for the PKK, its tepid response to the civil war in Syria, and its reaction to the overthrow of the Morsy government in Egypt. The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and Islamists in Turkey are allies of decades duration; likewise, there is no doubt that in his past Erdogan was a Muslim Brother and likely remains so in spirit if not in actuality. Thus, Morsy’s defeat was a shattering coup de main.

The Washington Post on 13 July 2013 published Charles Whitlock’s article, “US millitary drone surveillance expands to other hot spots…” Among other things, from the article we learn that some two score Americans administer “flight services” for the drone program operating from a small enclave found within the huge air base at Incirlik. What the team is up to, and how the continued presence of US drones at Incirlik benefits the Erdogan government – and in Washington what quid pro quo is at play as the United States makes use of the Turkish airbase to support drone operations — is still anyone’s guess.

OIL: The Constant Complicatrion

There are good humanitarian reasons for the US and Iraq to support an independence of sorts for Eastern Syria. In fact, there is good reason why Turkey might also support such a movement. And the rationale can be found in the presence of oil, that century-old Middle East hobgoblin.

At issues is Block 26, (see map, below) which is under concession to Gulfsands Petroleum Plc., and Sinochem International Oil Co., both of the U.K. The concession itself is a large (5,414 sq. km) and very promising oil field. It is potentially, a major gas producer, but information dealing with that resource are tightly held. However, the very promising oil field ceased operation, and it is currently in force majeure owing to EU sanctions imposed on Syria on 1 December 2011.

The development and operation of its Khurbat East and Yousefieh fields had been undertaken by Dijla Petroleum Corporation a joint operating companyformed between Gulfsands, Sinochem and the Syria’s General Petroleum Corporation (“GPC) the fields’ output was transported 20 miles by pipeline to the GPC-operated gathering facilities at Tel Addas. Blended with the Syrian Heavy crude oil, the GPC transported it to the Mediterranean port of Tartous.

With the imposition of sanctions, Gulfsands immediately issued a declaration of force majeure and has since has had nothing to do with Block 26. Regarding its Khurbet East oil reservoir, as the company noted in 2013, the output at Khurbat when possible has been excellent, and “since inception the field has provided approximately 19.3 million barrels.” The Yousefieh field practically ceased, with only 46 days production in 2012. Up to December 2012, cumulative production from the Yousefieh field since inception was approximately 1.3 million barrels. In February 2012 the Company announced that it had decided to cease all further exploration in Syria.

The concessionaires are in possession of a substantial quantity of high quality 3D seismic data over the Block 26 area that, it is hoped, will enable the Company to target further prospects should peace come to Syria – or to northeastern Syria.

The Nabucco Project

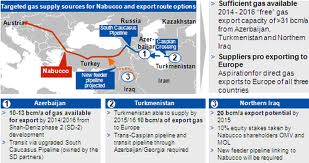

The possibility that Turkey might accept some sort of autonomy for Syria’s northeast can be found in the essentials involved in the construction of the Nabucco pipeline. Since the Nabucco project was initiated in February 2002. Since that date, the project has expanded into Central Asia and the Middle East

For a number of reasons, most relating to problems existing with the movement of gas from the Caspian fields, the Nabucco is still incomplete. The construction of the Nabucco pipeline (with maximum capacity of 31 billion cubic meters) was supposed to begin in 2013 and movement to Europe was to begin in 2017.

In 2012 the European nations began to consider the movement of natural gas by pipeline from Iraq’s Kurdistan fields through eastern Syria to connect with the Nabucco project pipeline that crosses eastern Turkey. (See map, above) The consortium still believes that gas from northern Iraq is an “option” to supply Europe. “Why shouldn’t we pipe gas from Northern Iraq?” Nabucco spokesman, Christian Dolezal is quoted as saying. “We should explore that as an option to secure future gas supply for Europe.” It is obvious that while the consortium is still determined to move Caspian natural gas to Europe, any alternative, including the connection of an Iraq-Syria pipeline through the Kurdistan region would be welcomed in Ankara.

Oil, like politics, makes for strange bedfellows – or at least the Syrian Kurds can hope so.